« Kira Lewis Jr. is the future

The Pelicans Are Improving On Defense »

Rebuilding Mistakes Part 1: When Teams Just Can’t Let Go

Winning in the NBA is hard. There are no guaranteed paths to sustainable winning or a championship, but there are many pitfalls along the way that make the task even more difficult. This series will examine common mistakes made by teams during their rebuilding phase. NBA history is littered with failed rebuilds so one doesn’t have to look far to find mistakes. The key is not just looking at the usual suspects on the never ending treadmill of woe, but also at the teams who have made it over the hump but hit a ceiling due to fumbles along the way. This will be a three part series, with the final installment releasing the week of the trade deadline.

When Teams Just Can’t Let Go

Case Subjects: Denver Nuggets, Sacramento Kings, New Orleans Horn-Pels, and basically almost every team at some point

One of the biggest mistakes I have seen teams make is overpaying to retain good but not great talent while the team is still bad. This predicament isn’t exclusive to bad teams, however, bad teams are in a much more precarious position compared to good teams or contenders who are forced to overpay key role players to keep their contention window intact. The effects of these decisions often aren’t apparent immediately and take several years to pan out. Let’s go back in time to the Denver Nuggets and see how some poor decision making in the past ended up burning them in the future.

In October of 2014, the Nuggets were at the tail end of their offseason and approaching the deadline for rookie extensions. On their roster was a young Kenneth Faried, age 24. Faried was coming off a season where he averaged 13.7 points per game, 8.6 rebounds per game, as well as a successful campaign with Team USA at the World Championships in Spain, where Faried was a gold medalist. The Nuggets had notched a 36-46 season after Andre Iguodala had left the team and Danilo Gallinari had missed the season due to a torn ACL. The Nuggets, optimistic of their ascent, decided to extend Kenneth Faried for 4 years, $50 million before his rookie contract was over.

While I can’t speak for the Nuggets brass, common sense suggests they were eager to retain a rising young player for the long term. And why not? Talent is difficult to acquire in the NBA, particularly if you are a non-premier market. Giving away or giving up on talent isn’t exactly a formula for winning. Nevertheless, the Nuggets finished that season 30-52 and fired coach Brian Shaw mid-season. The following summer, the Nuggets hired Mike Malone as head coach and went 33-49 and 40-42 over the next two seasons. At the conclusion of the 2016-17 season, the Nuggets were in a similar position to 3 years prior – they were an ascending team looking to extend a talented young player in Gary Harris. Sure enough, the Nuggets gave Harris a 4 year, $84 million extension in the summer of 2017. Something to note – the Nuggets had just drafted Jamal Murray (7th), Juan Hernangomez (15th), and Malik Beasley (19th) just one year prior in 2016.

Once again, the Nuggets had doubled down on retaining good but not great talent at a market premium, while they themselves were currently not a good team. Well the Nuggets eventually did end up good. They went 46-36 the next year, just barely missing the playoffs in a stacked Western Conference, and followed that up by going 54-28 and finishing 2nd in the West in the 2018-19 season. Nikola Jokic, and to a lesser extent, Jamal Murray, had arrived. So the Faried and Harris extensions helped right? Let’s take a look at the domino effect from those decisions.

Less than a year after the Harris extension, the Nuggets found themselves in an averse place regarding the luxury tax – a situation entirely of their own doing. Ownership was clearly not willing to foot a tax bill for a non-playoff team and instructed management to shed salary. The Nuggets had to attach a first and second round pick to Kenneth Faried, who was barely in the rotation at that point, to shed his salary. To a lesser extent, they also had to attach a 2nd round pick and a 2nd round pick swap to move Wilson Chandler (another good but not great player), who they had re-signed in July of 2015, coming off a 30-52 season.

The Gary Harris extension took less than a year before it was forcing Denver to attach picks to shed a previously poor decision. Meanwhile over the next few years, first round prospect Malik Beasley essentially remained glued on the bench while Denver tried to figure out what was going on with their $84 million man. Benching Harris for Beasley probably would not have gone over well in the locker room, and to outsiders the Nuggets would lose almost all trade value if they so publicly gave up on their high dollar player. Three years later, as Denver stared down the barrel of Beasley’s (and Hernangomez’s) upcoming restricted free agency, they decided they could not afford to re-sign those players and traded them away for what amounted to the 22nd pick in the 2020 draft and salary filler.

From a pure value perspective, Denver traded away the 15th and 19th picks in the draft for the 22nd pick. From a player perspective, they traded away a better player than Gary Haris in Malik Beasley all because they neither had the minutes for him (Gary Harris was taking them), nor the money (Garris Harris strikes once again!). Beasley is now averaging 20.5 points per game on a contract that has a cheaper AAV than Harris’, while Harris is having his worst year since his rookie year and is due over $20 million next year. This is just the impact on the surface. How many deals has the Harris contract cost Denver? There’s enough intel out there to suggest his contract was an obstacle in Jrue Holiday trade negotiations. From all perspectives, the Faried and Harris deals were costly ventures for Denver.

Denver Is Not Alone

Virtually every team at some point has made this mistake. I have two more examples from the recent past to illustrate the costly nature of committing big money to retaining good, not great, players while the team is still bad. Let’s take a look at the Sacramento Kings – a team which can be used to write an entire textbook on bad rebuilding decisions. In 2018-19, the plucky Kings had their best season in 12 years, finishing 39-43. Riding off the good feelings for that season the Kings re-signed Harrison Barnes, a good but not great, player to a 4 year, $85 million. Feeling good, the Kings doubled down and extended Buddy Hield (yet again a good but not great player) to a 4 year, $94 millon deal.

The Kings essentially invested $179 million for the privilege of keeping a 39-49 team intact. Similar to Denver and Malik Beasely, the Kings knew they had a pay day for Bogdan Bogdanovic pending, as well as De’Aaron Fox’s restricted free agency around the corner in a couple years. Well the Kings ended up losing Bogdanovic for nothing. Bogdanovic was already unhappy with his role behind the recently extended Buddy Hield, and the Kings did not want to complicate the matter further by matching the offer sheet Atlanta put forth. The Kings even kicked tires on Buddy’s trade market to no avail. By the way, they also drafted Tyrese Haliburton who has to compete with Buddy for minutes. It’s March and the Kings sit at 13-21, off the heels of a brutal loss against the Charlotte Hornets. Is this a team worth keeping together?

Like the Kings, Pelicans fans should be all too familiar with overpaying to keep a good but not great player while the team was bad. In the summer of 2012, the then New Orleans Hornets made a decision that would continually shape the Anthony Davis era. The 21-45 Hornets matched the max contract offer sheet Eric Gordon had secured from Phoenix. While I won’t dig up past traumas for New Orleans fans, the Gordon contract proved to be an obstacle in team improvement at nearly every stage. New Orleans reached the playoffs only once during Gordon’s tenure. How differently would things have gone had the Horn-Pels not had Gordon’s max salary on the books for the duration of Davis’s rookie deal? One can only imagine.

Lessons Learned

There are many cognitive biases and behavioral economic principles at play here that cause organizations to behave in ways that sabotage their future. From the inability to accept sunk costs to the endowment effect – where teams overvalue what they already have as opposed to what they don’t – teams repeatedly fall in these traps. Misjudgement of value is at the root of almost every bad decision and this study looks at a very specific mistake where teams double down on poor roster construction. It’s one thing to open the purse for a key cog on a contender (cough cough Malcolm Brogdon in MKE, cough cough James Harden in OKC), entirely another to do it for a team several games below .500.

Organizations tend to overestimate the importance of non-star level players on bad teams and often fool themselves into thinking improvement will occur naturally over the course of the second contract. Seth Partnow of the Athletic writes, “This, in turn, has the effect of players getting sizable rookie extensions or second contracts when, best case, their team is about to outgrow those players being high-priority options. Suddenly, when the team needs to add some wing defense, the cap money is all gone!” Seth was discussing this more in the context of teams spending more on “bucket getters”, but the logic applies all the same. Paying to retain good not great talent on a bad team gets disproportionately costly when the team finally gets good.

So how does a team get good without keeping good players? This catch-22 is one NBA teams find themselves asking before they inevitably commit long term money to keep their own players. It’s not really a catch-22 though. Sure, I understand that each team has different priorities with respect to winning, and there are ownership factors to account for. However, three avenues to add talent remain – the draft, trades, and free agency. There’s a lot of luck involved in both the draft and free agency, but in a league that has greater than 70% roster turnover every three years, trades will always be available for the opportunistic. Each year there will be teams looking to sell, buy, or simply shake up. My draft research suggests that a player may actually have peak trade value after their 2nd year on their rookie scale. If teams want to import good players, being more aggressive with trading young talent before their restricted free agency is one way to do so.

Can this approach open the door for missing out on your talent making a leap down the line? Absolutely. Growth isn’t linear and it’s very possible that the good not great player develops into a great player. However, the organization making this call needs to be cognizant of any biases leading them to make this decision. I’d also wager that over the course of history, you’d come out ahead if you always moved the player vs if you always kept the player. More often than not, the leap doesn’t happen and the improvement is simply incremental. This can still have damaging long term effects when building a team if the resources allocated to that player are actively impeding the team from adding other, better players. It’s the basketball equivalent of a player so afraid he won’t get the ball back that he takes a bad shot, rather than making a pass and trusting a better shot will come.

Lessons Applied

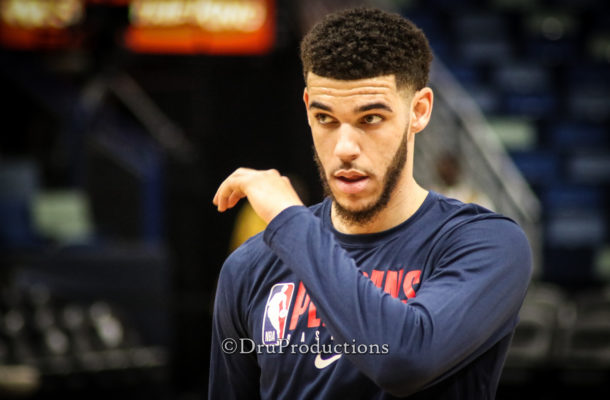

The Pelicans head into the trade deadline with Lonzo Ball and Josh Hart as pending restricted free agents. At the time of writing, the Pelicans are 15 -19, not exactly a good team. Brandon Ingram is already on the books as a max contract, Steven Adams received a 2 year, $35 millon extension, and Eric Bledsoe is owed $18.1 million next year. The team is already getting pricey without Ball’s and Hart’s second contracts on their books. The Pelicans are at a stage where they need to ask themselves if it is worth it to retain Ball and Hart on a team that clearly isn’t good. Are Hart and Ball so important to a 15-19 team that their skills need to be retained at 2-3x their current annual cost?

Personally, I’d be aggressive in fielding offers for both players. While sign and trades are technically a possibility, the biggest window to reap value occurs in three weeks at the trade deadline on March 25th. Hart may be a bit of an easier case to let play out in restricted free agency than Ball. His qualifying offer is only $5.2 million to Ball’s $14.3 million, and his cap hold is less than a third of Ball’s $28.7 million. It’s entirely possible that Hart doesn’t receive lucrative offers in restricted free agency and the Pelicans are able to retain their talent at very nominal cost, but are you willing to take the same gamble with Ball?

Between Ball’s large QO and cap hold, there is already an opportunity cost in place by letting him reach restricted free agency. What happens when Ball’s contract is on the books for $18-22 million per year for the remainder of Zion’s rookie contract and beyond? The Pelicans have already all but committed to being an above the cap team for the rest of Zion’s rookie deal, and the team will only get more expensive. So I ask again, how much is it worth to you to keep a bad team intact? What deals will re-signing Ball cost you in the future? Does a small sample of good play warrant foregoing potential assets at the deadline and optionality in the future? These questions might be impossible to answer today, but are the exact ones the Pelicans’ brass needs to be asking. There is little question that the Pelicans will one day be a good team with how rapidly Zion is ascending, but will it end up being in spite of Ball? Unless the Pelicans plan on importing a large amount of talent externally over the next few months, I worry what a large commitment to Ball will do to future flexibility. When in doubt, don’t Gary Harris it.

3 Comments