« How the NBA Returns: A Proposal to Save the Season

Kiss my ass, COVID-19. It’s Pelicans Day »

What Is The Best Way To Draft?

The goal of this project was to use historical data to inform draft strategy. The data set used in this article includes 502 first round picks from 1999-2015 and 991 veteran minimum contracts from the same time period. What began as a fun way to get back into the world of python and data manipulation became a project that took on a life of its own during this long hiatus from NBA basketball. This article looks exclusively at first round picks. At one point I decided data was not enough to tell the whole story. I decided to reach out around the league for expert opinion on the topic. This article features quotes and analysis from one League GM, one high ranking League Executive (from a different team of course, both agreeing to speak on the condition of anonymity), and Ben Taylor, author of ‘Thinking Basketball’. For clarification purposes, the GM will be referred to only as the GM, while the Executive will be referred to Executive or Exec.

The draft has long been a subject of fascination among fans and media. For teams, however, the draft is a crucial pipeline for talent. Teams that struggle to land stars in free agency largely rely on the draft to provide star level talent. Perhaps no team or executive has taken this basic ideology further than Sam Hinkie during the Process™ era Sixers. Nevertheless, there is a lot of intrinsic value in rookie scale players even if they never hit star level output. Drafted players can be cheap sources of production and come built in with mechanisms of cost control leading up to restricted free agency. The GM I reached out to, agrees –

“As you are well aware, the average PPV of rookie-scale players that produce above replacement is typically significantly higher than their salary number, even if they are picked in the 20’s and even if they are marginally better than minimum replacement players,” says the GM. “Hitting on someone in that 14-24 area is enormously important, both short and long term. If they are truly successful, the mechanism of restricted free agency allowing you to hold on to them in the case of a first-rounder, vs. losing restricted rights after three seasons with a second rounder is paramount from a team-building perspective.”

The point the GM makes about picks out-producing minimum level players is an important one we will come back to. However for all its importance, and all the resources poured into the draft, teams are still hit or miss when it comes to selecting players who will be successful. Part of the issue here is defining success – after all, shouldn’t success be measured by how much the draft pick produces for the team that drafts the player, or how much they return in a trade? The League Executive to seems to think so.

“I’ve worked with a number of executives that wanted to define success how a player’s career ultimately turned out,” says the Exec. “There were guys they had picked that didn’t turn out on the initial team that turned out later, but of course that’s not exactly, in my opinion, right. Because if the guy doesn’t end up contributing in any significant way for your team then it’s not that great of a pick for your team.”

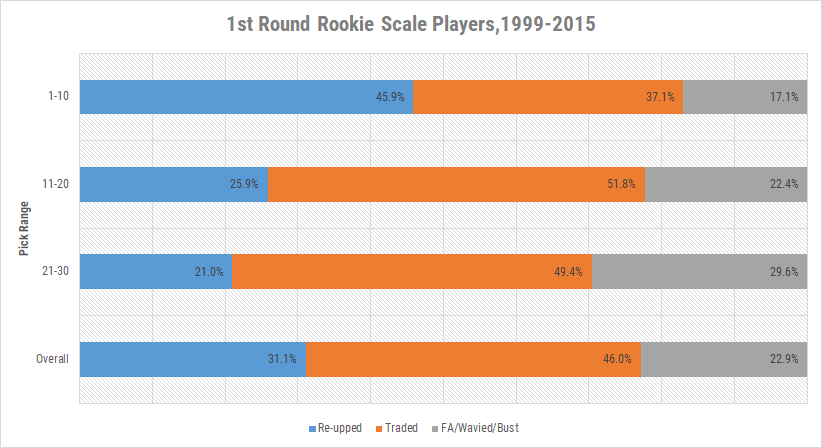

And so I turned to the data to see just how many first round picks actually made it to a second contract with the team that drafted them. Answer? Only 31.1%

The odds of a team re-upping a drafted player were significantly higher if the player was drafted in the top-10. In fact, the top-10 made up exactly 50% of all 156 players (out of 502 total) that were re-upped. Additionally, my research showed the odds of a player being traded not only increased significantly outside of the top-10, but also as the player’s career went on. Over 64% of first round players traded (a total of 321 out 502 were traded overall) during their rookie scale contract were traded in their third or fourth year, compared to just 8.2% traded in their first year.

Overall, almost 70% of the players teams draft won’t be on the team at the conclusion of their rookie contract. This was a tad surprising to me given how draft picks are touted as the gold standard of assets. Given this data, the true hit rate of draft picks is likely significantly lower than any retrospective analysis conducted solely on the career success of a player and compared to their draft slot. It also suggests that teams aren’t as great as extracting value from rookie scale players as we might expect them to be.

If teams aren’t great at this, then is there a strategy, driven by the data, that can potentially yield better results? My first instinct was that teams need to be way more aggressive.

Teams grapple with this question at a basic level when they discuss drafting a player that “fits” vs. best player available or player with the most perceived upside. Ben Taylor posits that some of the mistakes teams make can be attributed to drafting for fit. Especially when drafting outside of the top-10.

“The first issue is what these teams ‘need’ is often another star,” argues Taylor. “But when you narrow choices in this part of the draft you are then really hoping you can get a star-like player at the position that you need. That’s much harder – eg not every draft has high-quality stretch bigs in these spots. The next issue is that most of these teams don’t have a narrow window where they need a first/second year guy to play a role before growing. Most teams in that range need way more talent to compete, and if you get there, a role-specific rookie might be like an 8th man or something”

Taylor’s analysis resonates with my intuition that teams are generally too conservative when drafting outside the top-10. If teams are striking out, or not extracting value on rookie scale players as frequently as the data suggests, then why bother drafting for fit?

The Exec is a bit hesitant to dismiss fit outright. “I think that you do have to some extent have to take into consideration fit with the way your coach prefers to play,” counters the Exec. “Because I think if you’re a good organization, you’re winning, your coach is probably a cornerstone of your team. And you want to consider whether the player plays or could learn to play the type of style that fits well with your coach.”

But when it comes to drafting for a specific need on the roster, the Exec doesn’t necessarily think it makes sense to take that approach. “I think a lot of people will talk about drafting for fit or need, ‘oh they need a guard, or they need a big guy‘ things like that and I don’t really think THAT makes a lot of sense because when you’re drafting in these ranges, you should be considering the player may not be a contributor for at least a year, potentially two years if he hits at all. You can look at a lot of these guys who were good late first round picks and you don’t really see the player they are going to become until their third or fourth year in a lot of cases. Your team can change a lot.”

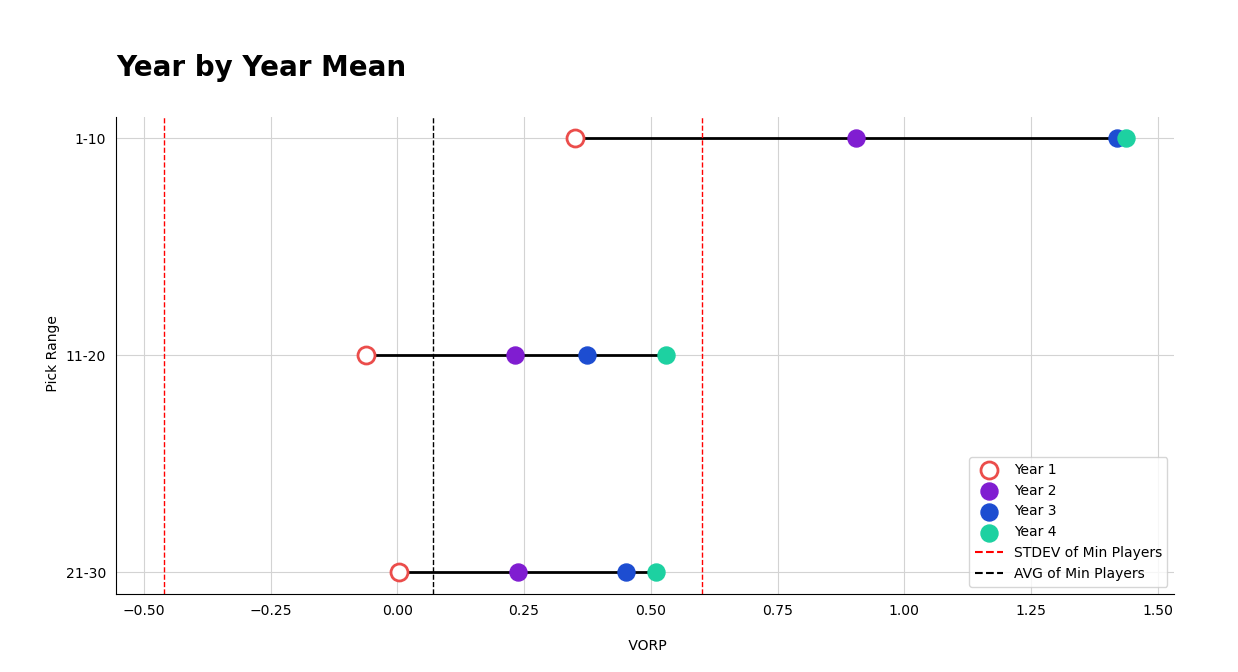

There’s a lot to unpack there. For starters, the Exec talks about how it takes a few years for picks to start contributing. But just how many years does it take and to what extent? I set out to catalog the yearly production of first round picks compared to sample of 991 veteran minimum contracts. Remember the GM talking about outproducing a replacement level minimum? Well I wanted to measure that. First, here is the distribution of VORP for all first round picks compared to min contracts. I chose VORP here because it is a cumulative stat that factors how much you actually play and because it is easy to extract from Basketball-Reference.

In this animated figure you can see the distribution of how each pick range performs against the distribution of minimum contracts. I included +/- one standard deviation from the mean of the minimum contracts to highlight that while some picks improve beyond this range, a good amount still fall within the expected range of a minimum contract after four years. The difference between top-10 picks and later first round picks is particularly highlighted by this next graphic which only looks at the means of each bucket, rather than the distribution.

Once again, I included the standard deviation of the minimum contracts to capture both the range of outcomes as well as illustrate how the average picks from 11-30 still fall in that range after four years. The data suggests that there isn’t a statistically significant (95% confidence interval) difference between minimum contracts and non top-10 picks for the duration of their rookie scale contracts.

The second part the Exec mentioned was that teams can change a lot by the time a player is ready to contribute.

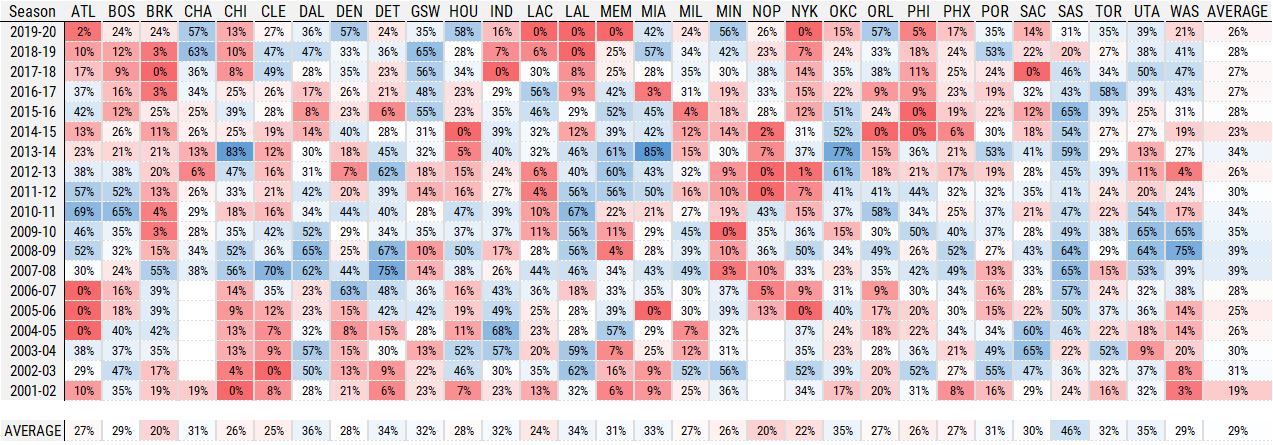

Just how much is a lot? I looked at three year roster continuity rate going back to the 2001-02 season. Continuity here is defined as the percent of a team’s regular season minutes that were filled by players from three seasons prior. For example the 2019-20 continuity is the percent of minutes filled by players who played in 2016-17 for that team.

The overall average for the league over the past 20 years or so has hovered around 29%. That means on average, three years from now, 70% of the team will look different. Get a load of the Spurs and their extraordinary continuity from 2004-05 to 2017-18 – it’s no wonder Gregg Popovich is the league’s biggest proponent of “corporate knowledge”, a term he uses to refer to continuity built up over years of experience within his system.

So if roster turnover rate is so high and young players take three to four years to develop, if they ever do, why would a team ever draft for fit? Clearly teams can get minimum level production, for well, the minimum contract. Shouldn’t the best strategy always be swinging on the high upside player?

The GM takes a more holistic approach.

“All depends upon where your team is from a rebuilding perspective,” suggests the GM. “If you already have young, elite play-creating talent to build around, then taking a player that “fits” a role that you have for them makes sense. If I would sign a vet minimum to be complementary, why wouldn’t I do the same with a slightly less proven, but significantly younger college kid? Historically, this is why great franchises seem to hit on later first rounders more often than “bad teams.” Most coaches aren’t capable of committing to a development plan for a “role player”, however and that can potentially derail an otherwise well-thought out draft pick.”

And that’s a fair point. Where a team is at in their rebuilding stage certainly matters. A contender might favor a proven commodity while other teams see no down side with allocating a roster spot to a young player that may turn into something, either on the court, or as a trade asset. Beyond that, how a coach chooses to integrate or develop a player can make all the difference in the success of the pick and is often why we see players find success in different systems or environments.

Despite this, in order to successfully execute the aggressive strategy of swinging for the fences you need the ability to reliably identify “high upside” talent. The league Exec isn’t sure teams are actually good at it.

“I don’t know that people have a very good ability to assess which players actually have the appropriate upside variance, you know?”, he argues. “In the sense that a lot of people might have said – Giannis may have been an easy one. Okay maybe people didn’t think he’d turn out very well but you could see the potential for some upside given that he had crazy length and feel at that size. Some guys that end up being among the most valuable, at least according to advanced analytics, like a Paul Millsap or a Draymond Green, or a Fred VanVleet to a lesser extent, these guys probably, not only were they not super highly ranked, but people who didn’t like them and even people who did like them would probably have termed them more as a safer, lower upside picks at the time.”

“Millsap and Draymond Green were undersized 4s that played four years in college, didn’t have elite physical tools or were perceived to not have elite physical tools. Even if your philosophy was – we wanna draft guys that have a 80th-90th percentile outcome that is really significant, more so than guys that are going to have an E’Twaun Moore career where you can check the boxes and say E’Twaun Moore, relative to draft slot was successful. Even if that was your philosophy where you actively try to do that, it feels to me people would end up being not very good at it. Even if you have the right philosophy in terms of understanding the valuation of really good players relative to mediocre players and how much that fits your franchise, I’m not sure that helps you necessarily pick the right players because I’m not sure people in advance can identify which guys are actually the high variance guys.”

Conclusion

The depth to which teams prepare for every facet of the game amazes me to no end. I went into this project with what I thought was a novel idea in terms of evaluating picks relative to minimum contract players. Instead, I was blown away by how teams have already walked down this path in much more detail.

Nevertheless, I found the data I collected was particularly revealing and supports my hypothesis of “don’t draft singles”. I also believe that teams are generally slow when it comes to moving on from an unproductive young player. If the data says that 64% of all players traded in their rookie scale contracts are traded in their third or fourth years, then supply and demand would dictate that a players value should be higher if moved by the end of their second year. Rookie scale contracts are set up like call options you can purchase on a stock exchange – a team with the contract has the right to exercise that option and buy in at a certain price point before things get too costly. The third and fourth year options as well as restricted free agency allow for teams to exercise that right. Trading a player before those options are exercised or before a player becomes extension eligible might return the most value – in fact, I suspect the value of the player rarely gets higher than its peak during the rookie scale. Whether or not this is actually true is a project I might undertake next with data I have collected.

Lastly, I want to thank the many people who helped make this project a reality. Without you this would be yet another idea lost in flow of a group chat.

2 Comments