Fatigue makes cowards of us all.

— George S. Patton, Jr, War As I Knew It

If you just look at the number of games or minutes played by the New Orleans Pelicans in the 2018-2019 regular season, you are left with the impression that the sample size is small, and that no conclusions . . . happy, sad, or otherwise . . . can be drawn. That’s likely true if you just look at the numbers. However, there is more information than what’s recorded in the box score or what exists only as rumor or innuendo.

The team is moving. No . . . not like the Sonics returning to Seattle . . . . The players are moving all over the court. They’re not just running, which is the common and not-quite-right description. The team is always “on.” The guy with the ball is moving, off-balls guys are moving, people are cutting, screeners are rolling. They are also hustling. On defense, as was on display in the Portland series, but also elsewhere, the players are pesky and frenetic. On offense, they are now grabbing offensive rebounds, too.

The results are impressive. However, I have a pretty standard response when people ask if I’m impressed with some feat: “if you want to impress me, do it again.” I’ve said this often, including about some of Davis’ scoring outbursts. It’s a flippant answer that’s meant to inject both a little humor and a little truth into the conversation. But, in this case, the point is this exactly: impressive as these wins and performances are, they do not matter if those performances can not be duplicated, at least in the spirit of play if not in actual results. There needs to be some predictive value to the performances when you describe them or they are simply reports of events that transpired.

Working Hard

How do we know the team is working hard?

- By watching them work (hard)

- Their pace is 107.2, 4th in the NBA

- Their offensive rebound rate is 30.6% (4th)

- Their defensive rebound rate is 82.5% (3rd)

The pace not being the top one in the NBA does not mean they are getting “out-run” or “out-worked” or “out-hustled” or whatever. None of them alone tells the entire story. Rather, the numbers work together to paint the entire picture. It’s easier to pick out extremes, which is why you see such things done often . . . so and so leads the whomever in whatever. This misleads the audience, and the analyst in some cases.

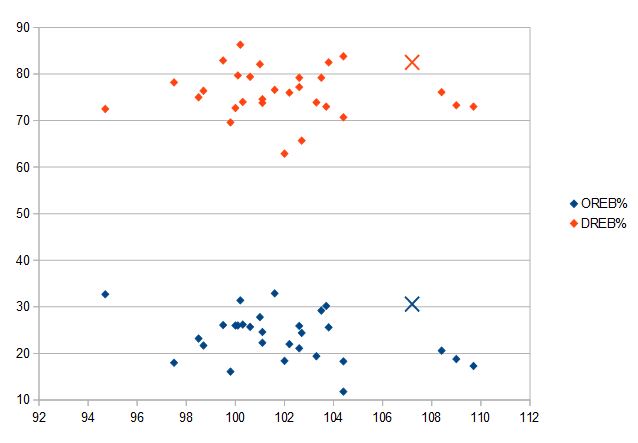

Here is a plot of pace, so far, in the NBA versus both OREB% and DREB%. You can see that the pace adjustment does a good deal to create a jumble of mid-pace teams, which makes sense . . . you can get middle paces in many ways. On the extremes, the underlying trends bite harder. That’s not to say only extreme rebounding should be tied to extreme pace, just that its difficult to “go” the other way than that the formulae say. Higher OREB% decreases pace since it lengthens the current possession rather than creates a new one, and higher DREB% increases pace since it creates a new possession and ends the current one rather than lengthen that possession. Complicating this is any relationship between the rebounding categories.

The Pelicans are the X in each data set.

You’ll notice that they are above the trend in both cases, particularly in OREB% since they buck the trend. Remember when I said that this happening is difficult? The DREB%, while good, it is not surprising and is perhaps expected. That OREB% is surprising, however . . . and informative. That number might just have something important to say.

It’s also likely unsustainable for the reasons given above, both mathematical and in terms of the physical exertion these sort of small-sample performance would require to sustain. In fact, that might be part of what it’s saying.

Working Smart

One way to sustain this is to just be awesome and never get injured. That would work, but let’s say, for the sake of argument, the universe does not cooperate. Then what? You can’t just exert your way to exertion. There is a wall.

Underneath it all, the success, while founded on the style of play, comes directly from the scoring. The Pelicans lead the NBA in FG%, 2P%, eFG%, and TS%, and are second in 3P%. That may not sustain across the board, of course, but it certainly will not sustain if the team loses its legs. If the scoring stops, the winning and domination stops. At that point, maybe the resolve to play this system cracks, maybe not. So, the smart thing to do is get ahead of the beast and head it off at the pass by limiting the fatigue, in-game in particular. You need to control the game-to-game fatigue, but that has gotten more emphasis around the NBA in recent years; there is no need to address it here.

Since each minute of play is more taxing in this style that relies on defense, power, energy and a cacophony of passing, it may seem that limiting minutes is the answer. Maybe it is a factor, and getting up and forcing the opponents’ concession is a great way to shave off minutes for major players, but that tactic to limit minutes does not help if it can not sustain to that point. Taking minutes away from better players and giving them to worse players without a good reason is foolish, so shaving minutes off the end when the outcome is decided is the only way this makes sense.

The move is then to break up the minutes played in more of a staccato fashion, setting a ceiling on each player’s playing stint in the “regular” portion of the game. You would simultaneously set a floor on the player’s rest stint. These may very from player to player, and they may change as conditioning improves over the season. You would also see exceptions in certain games and situations.

In the jumble of all this, you may find the need to have two of the three primary bigs on the bench. This means you need to either play small for a bit or play Okafor more. Either way, the example shows that the rotation should not be the 8-man rotation we saw in Houston (a special case) and maybe more than the 9-man rotation against Sacramento. Gentry addressed lengthening the rotation to 9 or 10 while speaking Sunday at practice, by the way.

Here’s what I hope to see:

- Start with a normal rotation, set the tone, gwt some wins, make everyone believers, and let them feel the fatigue

- Tinker with the rotation, perhaps lengthening it, to control playing stints and rest stints

- Sustain this for many weeks, maybe some slight tinkerings

- Begin to shorten the rotation to measure conditioning, improve it, and prepare for the Playoffs

- Short rotation in the Playoffs, aside from tactical matchups

Additionally, I think this may be done during each half, since there is significant, blanket rest for all players at halftime. This may be why we saw the Pelicans surge at the end of the first half of each game. Neither game was really competitive at the end, so while we did not see them go hard until the very end of the second half (though pretty late in Houston), one has to believe that if necessary, they would. Jrue and Elfrid said this emphasis is a conscious choice, but they are hoping to increase their consistency so the choice is not necessary.

Michael McNamara just wrote about why Gentry needs to explore the three big men playing together. Lengthening the rotation is likely necessary to enable this, but so is controlling the stints for which each player is in the game. The tinkering I expect to see is a great time to check in on the three bigs playing together.

Additionally, while the pace may cool as the season wears on, it should still be high and the Pelicans should hope to be playing that hard. The high pace is in part due to trying to get a shot before the defense is set. While this is strictly speaking about taking early shots, it’s really about getting the ball down to a relatively open man quickly. If limiting the pace serves to limit these opportunities, this is throwing the baby out with the bath water. Those possessions are precisely the type they hope to generate. Keeping players fresh while keeping the best players on the floor as much as possible is a tough task given all the variables in play.

These are all things to watch as they further explore this brand of basketball.

Statistics per basketball reference, gathered on October 22, 2018.