« Season in Review: Kendrick Perkins as the Good Influence

Season in Review: Alexis Ajinca slipped a bit »

Season in Review: Ryan Anderson is a Veteran

Ryan Anderson originally came to New Orleans as one of Dell Demps’ “young veterans.” As you can probably recall, the idea was simple. Bring in a bunch of youngish guys that have a little professional playing experience. This was supposed to fast track the team’s success, while still keeping the Pelicans’ championship window relatively wide. Well, much has happened since then. No one on twitter calls Dell Demps “Dealer Dell” anymore, and Ryan Anderson got older.

Sure, he is only 27, but the important part of NBA youth, the potential for growth, seems to be over for Ryno. That doesn’t mean we should be disappointed or expect Anderson to start regressing. No, this is simply a fact of life. Players eventually become who they are, and we have to update our short and long run expectations after this moment has passed.

Of course, I could be wrong, and it won’t really change anything. Anderson could make a huge leap in the next few years, but at his age, position, and play style, the probabilities are against him. On the other hand, he is likely entering his prime so the best may be yet to come, but it won’t look all that different from what the recent past has looked liked.

Normally, we could ignore these little details, but as we all know, Anderson is due a big pay day this summer. The question for the Pelicans seems simple; is he worth it? Frankly, it’s more complicated than it sounds, and this post won’t take a stab at answering that question. Instead, we will lay the ground work by simply doing the descriptive analysis of what kind of player Ryan Anderson was in 2015-16.

Background

2015-16 was a contract year for Anderson, and it was his healthiest season since 2012-13 when he played in 81 games. Of course, Anderson may have played in more games, but he was effectively shut down with just over 10 games left to play.

The raw stats were also pretty good for Anderson. Per 36 minutes, he averaged 20.2 points, 7.1 rebounds, and 1.3 assists. His advanced stats tell pretty much the same story, though the evidence isn’t as emphatic. For example, his PER was 17.1 last year, which is solid and decidedly above average. Still, it was a point or so below his peak seasons during his last years in Orlando and first years in New Orleans before his awful injury.

This seems to be the major take away from this season for Ryno. If last year was all about proving he could come back, this year seemed to be more about getting back to normal. His PER improved. His field goal and 3 point percentages moved closer to his career averages, and he just looked more comfortable on the floor. Of course, this is only a cursory glance. Let’s take a deeper look at some of the data.

The Gap Between Home and Away

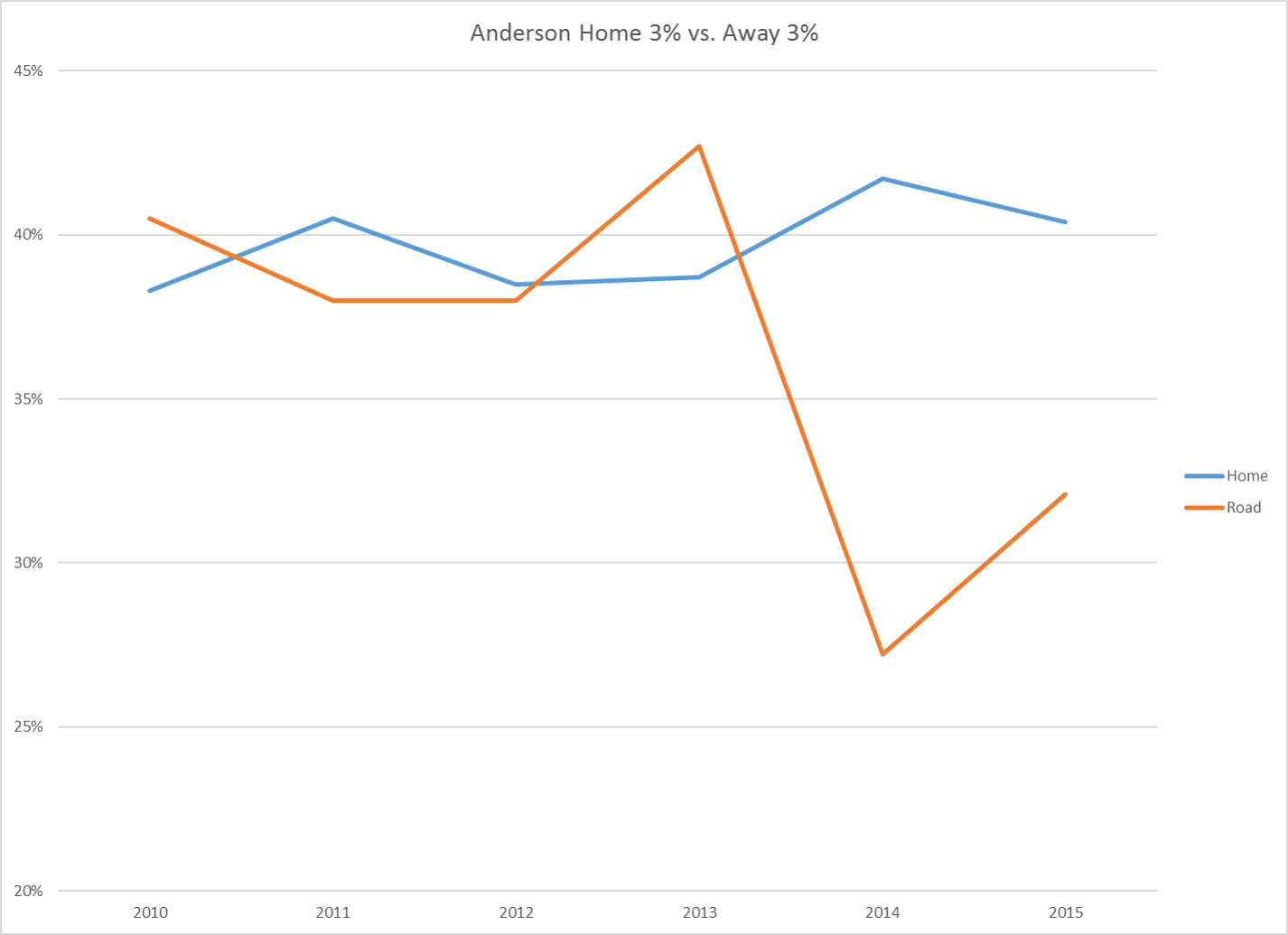

Ryan Anderson is better at home. Well, more specifically, he is a better shooter at home, but since so much of his value as a player is tied to his ability to hit threes and stretch the floor, this seems like a reasonable shorthand. It is also the type of statement that statisticians and numbers folk love to stress test, because statements like those seldom completely hold up. I mean, of course, some players play better under different circumstances, but it can be hard to test and determine whether that difference is purely coincidental or indicative of a real relationship. Also, most players and team’s perform better in front of the home crowd. Who’s to say any particular player benefits more from their home court than another? Well, in Anderson’s case, the debate seems just about over.

Since 2010, Anderson has only shot better from 3 on the road twice looking over whole seasons. First, he did it in 2010, when he was playing in Orlando. The second time came in 2013 when he only played in 22 games, so we have a notable small sample size asterisk there. Overall, however, we actually have a lot data in terms of games, minutes, and shots that suggest Anderson is just a little bit better at home. This was a trend that continued in 2016.

I feel like a lot was made of this difference in home and away this year, but the funny thing is that the gap actually improved from last year. That is, the gap between Anderson’s 3 point shooting at home and on the road was only 8.3% compared to 14.5% last year, according to basketball reference. Oh, and overall he shot better in 2015-16 than in 2014-15. So yes, Anderson shoots better at home, but the last two years have been particularly bad, given the historical data.

Again, I would hesitate to say this improvement will continue until his percentages are equal at home and on the road, but it seems reasonable to think it may go back to old levels of a ~2% to ~4% gap between home and away. Also, we still have a few other questions to answer before moving on.

Again, I would hesitate to say this improvement will continue until his percentages are equal at home and on the road, but it seems reasonable to think it may go back to old levels of a ~2% to ~4% gap between home and away. Also, we still have a few other questions to answer before moving on.

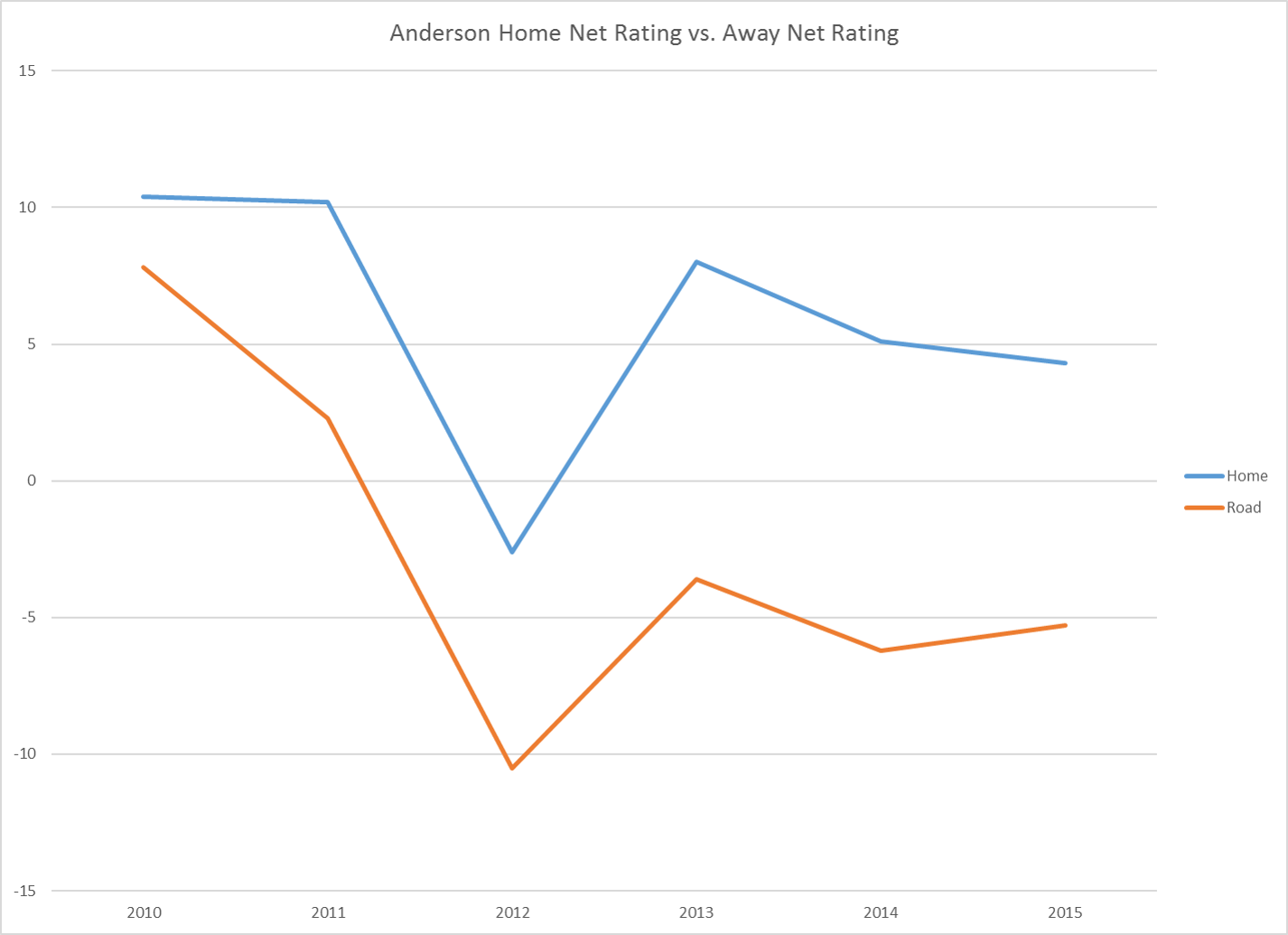

First, does this gap in performance extended beyond shooting? Actually, when we look at Anderson’s net rating (i.e. the difference between his offensive and defensive ratings) the trend only becomes more clear.

As you can see, Anderson has performed better at home than on the road… But, there are probably more than a few confounding variables here. First, almost every team performs better at home, and a player’s performance can be heavily affected by the guys he is playing with. Really, we aren’t seeing anything we wouldn’t really expect from most other players.

So, yes, it would appear that Ryan is better at home, but the gap, in the long run, probably isn’t as wide as it has been the last two years. More importantly, I don’t think there is much anyone can do about it. Shooting is about comfort and routine. It only makes sense that a player is more comfortable on his home court.

Mr. Steady

One of the trendier critiques of Anderson last year was that he didn’t score in bunches. The idea is that he often has games where he hits 1 or 2 threes, but he seldom goes off and ends up with 3 or 4 threes. This means, according to some, that he wasn’t as dangerous as other players, who did have games with a bunch of 3 point makes. Thus, he didn’t put as much pressure on the defense as those guys, and his value isn’t as high.

Before we look into the 2015-16 data, notice that we have run into a counter-factual problem with the above logic. Following the argument above, if Ryan Anderson did occasionally nail a bunch of 3s in a game, opponents would shift their defense to him, in an effort to limit his ability to take and make 3s. The fact that we aren’t seeing many of those high scoring games may actually be proof of how much pressure Ryno puts on the defense. The defense may have just already shifted their focus to him as soon as he walks on the floor, not after he’s already made a half dozen threes.

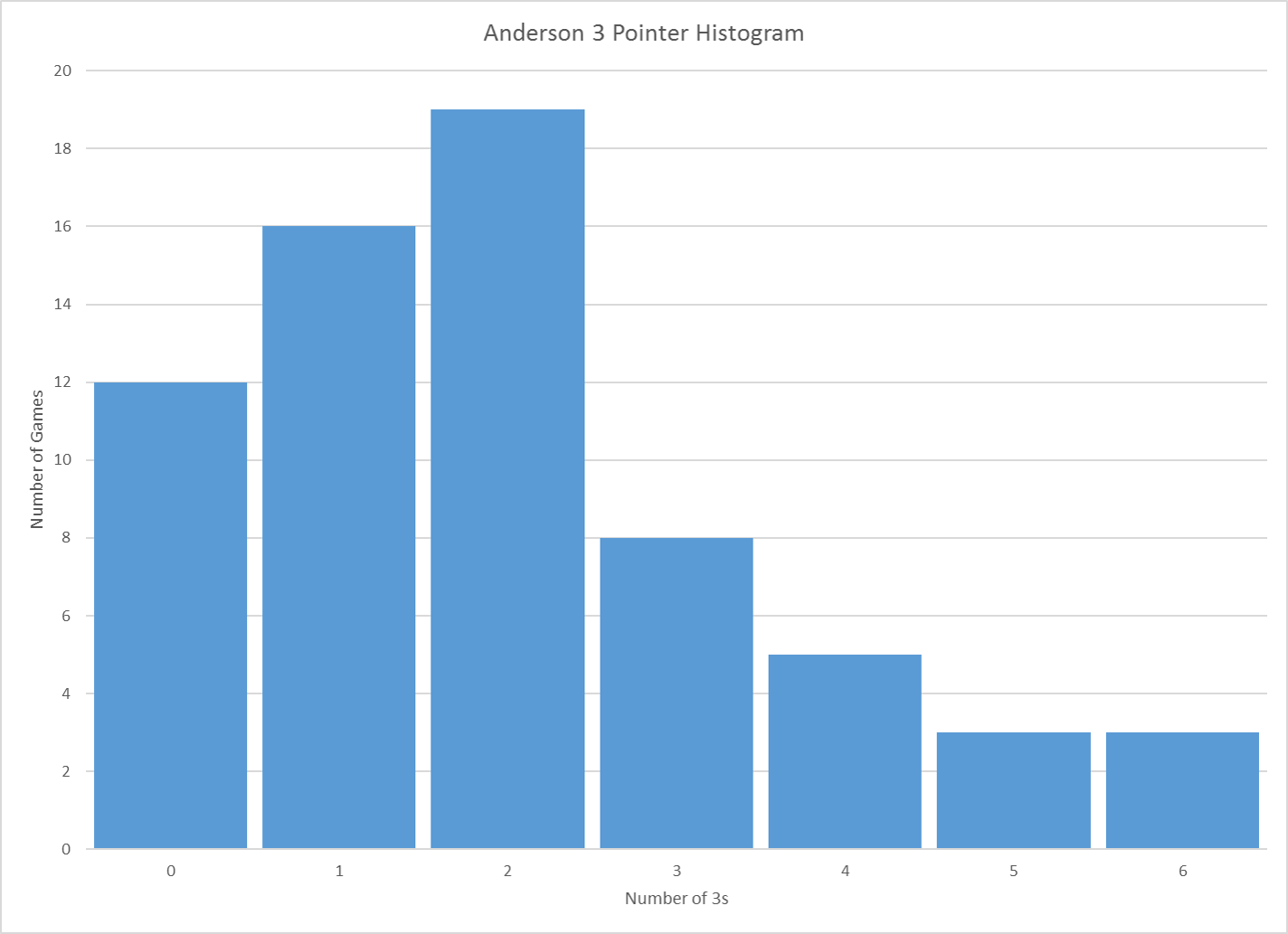

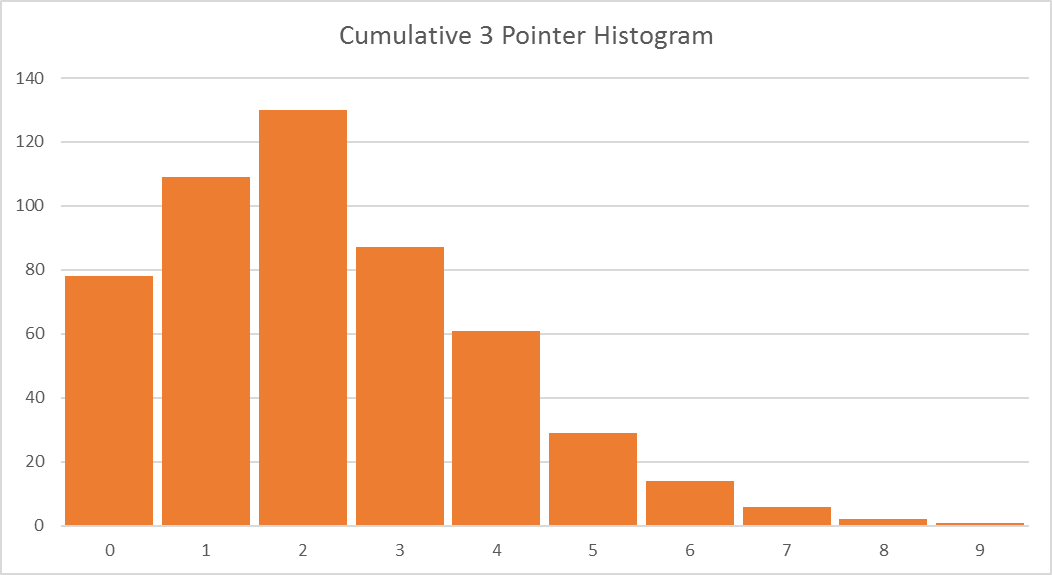

Back to the 2016 data. Below we have a histogram of how many threes Ryno hit in every game last season.

As you can see, Ryno hit 2 3s in a game more than any other number, which is a pretty solid expected performance (His average was 1.9 3s per games, by the way). It is also pretty clear that, at first glance, the commentary seems to be true. In 56% of his games last year, Ryan hit 2 or less 3 pointers, which follows the story line that he doesn’t often go off and hit bushels of 3s.

But is he really different than anyone else in the NBA? Consider forwards, as defined by basketball reference, who shot 35% from 3 last year and took at least 5 per game. That list includes: Trevor Ariza, Paul George, Kevin Love, Ryan Anderson, Robert Covington, and Nikola Mirotic. That’s a nice, short list of solid stretch fours in the NBA. Let’s look at their collective histogram from last year.

We did add a few more 6 3 pointers made games. We also had 7, 8, and 9 games show up, but the trend is pretty much the same as for Ryan’s individual chart. In fact, if you run some descriptive statistics on each player, you’ll see that Ryan is actually about middle of the pack in terms of volatility. That is, Ryan’s performances are more spread out than most of the guys on our list.

Ryan didn’t have a lot of high volume scoring games last year, but there aren’t many guys who do have those games. Oh, and if they do have those games, they occur very infrequently. For example, in our data set, 7 or more 3 point made games made up ~1.75% of the games in our sample set. We probably shouldn’t hold it against Ryan that he isn’t one of he best guys in the leagues at having big games. He’s solid, and solid is good enough for most role players.

The Final Takeaway

I started this off by saying that Ryan Anderson is no longer young. He’s a regular veteran now. To me, being a veteran means I know what I’m getting, and I’m less concerned about what you might developed into 3-5 years from now. In Ryan’s case, I know I’m getting some solid, if not elite, floor spacing. As we saw above, he has some deficiencies, and among an elite crowd, he can seem average. Still, he hits shots at a good enough rate and isn’t scared to take them. Those things have value.

But his game does have serious shortcomings. He can’t play defense very well, and he occasionally trusts his shot too much, which turns him into an unwilling passer. But, we all know that by now, right? That’s the thing with veterans. You know what they are and aren’t. There isn’t much sense in hoping they change now.

The biggest question for Anderson and the Pelicans is what comes next? Will the Pelicans make a move to resign him? Would he even accept their offer if they did? Do we want him back at all? I’ll give you an economist’s favorite answer: it depends.

Nevertheless, I enjoy watching Ryno play. I like having a guy to root for that seems like a good person. I wouldn’t mind another 3-5 years of him launching deep 3s, but I can also understand if it is time for both Anderson and the Pelicans to move on. Still, that won’t make watching this veteran leave any easier.