The stat line doesn’t tell the whole story, and if that’s all you looked at, you might think Eric Gordon has had a relatively consistent season. The truth is that Gordon has been up and down. He’s had a few incredibly efficient games, but he’s also put up a few stinkers. Variance in player performance is to be expected, and coaches and GMs certainly anticipate it. However, the real question is what is causing the variance? In other words, what is making a player go from playing like a quality NBA starter to then playing like a marginal rotation player?

NBA analytics guys often implicitly or explicitly attribute variance to randomness. When you hear someone say something about a player experiencing “regression to the mean”, they are essentially saying that whatever we just observed was not due to causality. Regression to the mean is more an idea of luck. So let’s say one night Eric Gordon goes 1-10 from 3, despite being a ~37% career 3 point shooter, and let’s assume his poor performance was just bad luck. He missed shots he would usually make. If we could perfectly replicate every situation in that game and play it over, we’d expect Gordon to make more shots closer and finish that game closer to his average. Nothing about the game has changed. His improved performance is really just a function of probability. Though it is a little reductive, we can think of it as simply being lucky vs. unlucky. (Side note: I think a lot of people actually mean the Law of Large Numbers when they use Regression to the Mean. They are very similar mathematical concepts, in a way, but they certainly aren’t interchangeable. That’s a post for another day).

Of course, randomness doesn’t always explain why a player has a good or bad game. In fact, there is often a causal explanation, even if they aren’t immediately clear. For example, if a player struggles against smaller and quicker teams, then we shouldn’t be shocked if they perform poorly against Golden State. That isn’t bad luck. That is a bad match up.

Here’s the issue with Eric Gordon. Last year, he played like an elite spot up shooter. This year, the story hasn’t been the same. He’s gone 1-9, and just last night he shot 4-5. Overall, he’s just hasn’t been as good of a shooter. Is this due to pure bad luck? Or is something actually happening on the court that has contributed to his inconsistent shooting? This requires a little bit of digging.

First, let’s start with last year. Gordon shot 44.8% over 61 games. If we remove last year’s and this year’s data, he is a career 37% 3 point shooter. That’s a pretty significant uptick over a large number of games and shot attempts. The knee jerk statistical interpretation would be that some part of that increase was probably luck but some of it was also due to better circumstances than previous years. In short, we have both some favorable randomness and some causality.

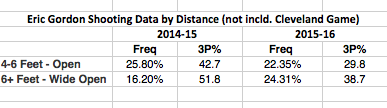

Looking a little more closely, we see that Gordon really excelled with wide open and open looks as defined by NBA.com/stats. Specifically, he shot 42.7% on open looks last year and 51.8% on wide open looks last year. If we remove the Cleveland game, those numbers are down to 29.8% and 38.7% respectively. The bizarre, though possibly encouraging thing, is that Gordon is actually getting more wide open and open looks per game. The problem has just been that he hasn’t hit them.

Now, this may suggest that we are seeing a bit of randomness or bad luck. Gordon is getting the looks he likes, but the shots aren’t falling. Still, there may be something else going on. So let’s keep going. Another thing that pops out in last year’s data, is that 93.3% of Gordon’s above the break 3 point attempts, his favorite spot, were assisted. This year that number is down to 81.3%, and that includes the Cleveland game, where all 4 of his makes were assisted and above the break.

Another thing worth mentioning is that last year Tyreke Evans was the passer on about 57% of those assisted 3 point shots. This season Ish Smith has filled that role a bit, but the results haven’t been as dramatic. Obviously, Gordon played a lot more minutes with Evans last year than any other guard, but even if we adjust the data to assisted 3 point attempts per 100 minutes, no other guards came close to matching Tyreke last year.

Before last night’s game, Gordon and Evans played 17.5 minutes per game together in 2 games. Last night, that number jumped to 23. So we have some evidence to suggest that Gordon shoots better with Tyreke on the floor, and Gentry may be responding to that evidence while still tinkering with his lineups.

Note that Gordon’s improved shooting performance with Tyreke may not just be about Tyreke finding an open Gordon. The way point guards pass can be much more subtle than that. For example, Tyreke might do a better job than our other guards at passing to Gordon in just the right spots and at the right times. He might also have a better sense of where Gordon wants to catch the ball, before going into his shooting motion. Those are things that are hard to quantify and parse out. Still, we’ve seen a pretty clear relationship between Tyreke and our other guards. He makes them better when he is on the floor. Lastly, it may be that the defense is also different when Tyreke is on the floor since his attacks on the rim need to be addressed, and that shifts the defense in a way that is favorable for Gordon.

Let’s return to the Cleveland game for just a second. If we go back to our original summary table and include the data from the Cleveland game, Gordon’s season numbers for open and wide open shots jump to 31.7% and 40.6% respectively. Of course, we end up with a similar problem. With a one game sample, it is impossible to tell if his performance was due to luck, playing with Tyreke, or something else. Granted, he won’t shoot that well over the course of the season. So some of it is certainly luck, but all of his looks were wide open or open last night. If that continues with superior passing, we may see a more consistent Gordon moving forward. Or we could have simply observed one outlier. At any rate, this is worth keeping an eye on.

One thing that has been left out is the effect of a new system and philosophy. This is another factor that could be contributing to Gordon’s slow start. Michael Jordan, when asked about how the game changed when he began to reach his prime, said that the games start to slow down for him. He didn’t have to think as much. That quote or story may be apocryphal, but the point is valid. Understanding the game and a style of play leads to players feeling comfortable. They don’t have to analyze. They can simply react. Perhaps, Gordon’s underwhelming performances this season were due in part to adjusting to the new system. Instead of reading and reacting, he had to read, think and then react. That extra step can cause a lot of problems.

So what Eric Gordon should we expect to see the rest of the year? Should we expect the Mr. Efficiency we saw against Cleveland or the inconsistent shooter we saw the rest of the year? It is impossible to say at this point, but there is evidence to suggest that both Gordon’s terrible and great performances are not totally random. The good news is that the data also suggests that the contributing factors for his great performances weren’t there at the beginning of the year, but they are there now. We will have to wait and see, but we do have some reason for cautious optimism.

2 responses to “Finding the Real Eric Gordon”

As soon as Gordon starts dribbling, bad things happen. Missed shots, blown layups, balls bounced off the front or back of his own foot, steals, grimacing and whining by him, and cringing from every fan in attendance. He thinks he is a baller, but he is really just a shooter. Couple that with his inadequate defense and his reboundophobia, and you can see why I’ll be pleased when he is gone from the team. He only does one thing well. While catch and shoot 3-pointers are a very valuable and fairly rare thing, I would rather have someone who can perform that part 90% as well, but do other positive basketball things at twice or thrice the rate and half the salary.

Getting EG contract off the books should be #1 on The Pelicans Christmas list.