That guy just finished watching his team play, and he’s screaming at the top of lungs.

No . . . he’s not happy . . . he’s clearly mad.

Yes . . . yes, that’s it . . . a last second bucket decided the game.

No . . . his team didn’t lose . . . they won.

No . . . this wasn’t the ABN, the `ball’ wasn’t a cube . . . this was actually on Earth . . .

This actually happens, and it happens often. Why?

In general, at some point the ultimate goal of a title for a fan’s favorite team is so far away, that fans turn to the distant future for hope, and offseason changes to their team are the vehicle for this hope. This is perfectly rational, especially when the onseason is a horror show. Foremost among these is the draft of new talent. In some sports, having the worst record guarantees the most valuable pick in the draft (though it’s up to the GM to use it to full effect), the second worst record guarantees the second most valuable pick, and so on. In the NBA, there are no such guarantees for teams missing the playoffs (those in the playoffs have guaranteed Draft positions), though all such teams have a chance at the most valuable pick in the Draft.

Thus, the “why” lies in the qualitative notion that a loss now, which is less hurtful than others since it occurs once the season is “lost” and the team is “going nowhere,” will serve to gather more wins in the future that will be of greater value than a win now.

This is all very logical.

And qualitative.

Qualitative analysis has a very important role in science and general thought (some is used below), but so does quantitative analysis (more is used below).

Meaningful Benefit of the Lottery

While it is true that losing games does not decrease your odds of winning the Lottery, it does not guarantee an increase, and any increase achieved is not necessarily very influential. Sure, an increase is a help toward the goal of winning the Lottery, and winning the Lottery has a very small downside in itself, but not all differences make a meaningful difference. The small costs are a slightly increased rookie scale ($0.5mish between first and second, another $0.4mish to third, and $2mish between first and seventh), which is inflated by 20% in most cases. Also, every pick has inherent risk of being an injury bust (e.g. Oden) or of not selecting the eventual-best available player (e.g. likely Bargnani). Since these are essentially ubiquitous, they are non-discriminators. As such, they do not enter than analysis.

While this is a clear net benefit if the team wins, the questions are

- How much?

- How big of an if?

How much winning the Lottery helps may be hard to measure, but we can develop a simple metric quickly. Clearly, winning games is discounted since the argument being made that this article is a response to is that winning games is not the highest good (otherwise this would not be a discussion).

So, we use winning titles instead. In particular, we count the number of Drafts where the top Draft pick won a title with the team that drafted him before departing the team. This seems to be the ultimate goal of many subscribers to the losing-is-winning school of thought, so it is fair, relevant, and reasonable.

Since the Lottery was introduced, exactly 2 of the 28 first picks in the Draft have won a title with the team that drafted them. Their names are David Robinson and Tim Duncan. Oh, and Robinson only won those titles when Duncan was there. And, only with Gregg Popovich, clear Hall of Famer. And, the Spurs were not structurally unsound as a franchise nor were they intentionally losing when they got the second of their top picks; Robinson was hurt. This is completely ignoring that Robinson was acquired in an unweighted Lottery.

Even discounting the last 5 Drafts just to allow time for the team selecting first to rebuild (which the Spurs did not), then in 23 Drafts, the 1 team won the Lottery twice 10 years apart and had a Hall of Fame Coach who also made that second first pick for them. The first first pick did not help the team win a title without those two other pieces.

That is not a strong vote of confidence in the actual value of winning the Lottery. Sound and fury, signifying nothing?

Any suggestions for objective metrics can be included in the comments, and I’ll publish the results if they pass muster.

The how big of an if question is easier to answer. The NBA Draft Lottery percentages are quite clear and only change in the case of a tie. Multiple picks can change a team’s overall chances, but that does not change the chances of a Lottery position converting into a particular Draft position. You can look at the chances yourself, but here are some key points assuming each team has a single pick and there are no ties (unless otherwise indicated):

- Each team’s most likely outcome, even if there are ties, is to draft outside of the top 3

- Each team has no more than a 0.25 probability of drafting with the first pick

- Only the top 2 Lottery positions have over a 0.5 probability of drafting in the top 3

- Only the top 5 Lottery positions have over a 0.5 probability of drafting in the top 5

- A team would have to occupy at least 3 Draft positions to have at least a 0.5 probability of drafting with the first pick

This is not a strong vote of confidence in being able to actualize the potentially-small net meaningful-benefit of winning the Lottery.

For those not convinced, here’s more detail.

Consider an experiment with 2 outcomes, winning and losing, with the favorable outcome (i.e. winning) having a probability of at least 0.5. We call this experiment with preference structure aligned this way desirable. This is because you are more likely to end up happy than sad. The net happiness can still be negative (so, net sadness) if the degree of sadness exceeds the happiness enough. This point rarely arises in the NBA Draft Lottery, so no biggie; it’s just something to keep in the back of your mind.

There is no reason to participate in an undesirable experiment without external pressure, but a desirable experiment is one that, given the proper resources, one should rationally entertain.

The NBA Draft Lottery, by this definition, is not desirable if “winning” is equated with selecting a player with the top pick in the Draft. In fact, occupying 2 Lottery positions does not make the Lottery desirable. A team needs to occupy at least 3 Lottery positions to make the Lottery desirable, and in that case only 5 collections of Lottery positions (of 364) make it so: (1,2,3), (1,2,4), (1,2,5), (1,2,6), (1,3,4). In other words, the top Lottery position then either 2 other top 4 Lottery positions or the second Lottery position either the fifth or sixth. Those rare collections net a probability ranging from 0.512 (from collection (1,2,6)) to 0.605 (from collection (1,2,3)). While desirable, it is not staggeringly so.

Another way to view the Lottery as desirable is to consider the `game’ over multiple iterations. So, if one has the top Lottery position, the Lottery becomes desirable if viewed as a collection of 3 independent`sub-Lotteries’. If one has the second position repeatedly, another Lottery is needed. Still another is needed for each of positions 3 and 4. Varying positions from year to year will have an averaging effect if one cares to estimate such fluctuations, but it is left to the reader as an exercise to determine that there is no point in scribbling all that down: the multiple year strategy is ineffective since most front office staffs do not have this long to wait to get their players then coach them up while maintaining team that is ready to compete..

The most effective way to make the Lottery desirable is to redefine “winning” as picking in the top n picks, notated as winning(n). Thus, most of the above is about winning(1), or needed to draft first to be considered a Lottery winner. In other words, lower the standards. This is fair, though, as many quality players have come from outside of the top pick in the Draft.

Ryan’s Value of a Draft Pick piece comes in handy, as it tells us that picking in the top 5 is way better than picking below it, so we draw a line in the sand there for the purposes of illustration. Also, once a team is in Lottery position 6, they are less likely to pick in the top 5 than out of it, necessitating a combination with strategies deemed ineffective (at least alone), so we only present Lottery positions 1 through 5.

The following table shows how many Lotteries are needed at a constant Lottery position to make the Lottery desirable as a function of the definition of winning.

| Winning(1) | Winning(2) | Winning(3) | Winning(4) | Winning(5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lottery Position 1 | 3 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 1 Lottery | Guarantee | Guarantee |

| Lottery Position 2 | 4 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 1 Lottery | 1 Lottery | Guarantee |

| Lottery Position 3 | 5 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 1 Lottery | 1 Lottery |

| Lottery Position 4 | 6 Lotteries | 3 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 2 Lotteries | 1 Lottery |

| Lottery Position 5 | 8 Lotteries | 4 Lotteries | 3 Lotteries | 3 Lotteries | 1 Lottery |

For example, if a top 3 pick is the target, then the Lottery is only desirable for a team in Lottery Position 5 if the team participates in 3 Lotteries.

Remember, this only gives at least a 50% chance of the outcome, not a guarantee. The guarantees are specifically mentioned). Lottery Position 5, Winning(5) has probability just over 0.55, for reference.

This redefinition of winning is a particularly useful one, and one that has merit. It recalls the metric used measure the net benefit of winning the Lottery, which was winning titles with that top Draft choice. It is inescapable that the number of teams that won a title with either of their top 2 Draft picks is at least as large as that same number when counting only top Draft picks (that number was 2, sort of). In fact, the number increases from 2 to 3 as . . . Darko . . . joins the list with Duncan and Robinson. He was on the Pistons 2004 title team. Kidd was drafted by Dallas in 1995 but left before winning the title with them in 2011.

Ummm . . . yeah.

Yes, yes. Free Darko. Happy?

Adding in third picks, we gain nothing. Sean Elliot left and rejoined the Spurs before winning a title.

Fourth picks give nothing either, and fifth kicks bring the total to 4, as Dwyane Wade is picked up (and he won with Shaq, mind you).

4 players. 4 players out of 115 top 5 picks in the first 23 years of the Draft, 140 top 5 picks if we count all 28 Drafts in the Lottery era. That’s counting Darko and has 4 mpg at a PER of 6, WS/48 of -0.049 in the regular season leading into his 14 total playoff minutes that season spread across 8 games in which he missed all 4 shots but did nail 1 of his 4 free throws.

Might I have missed 1 or 2? Yes. 5? Unlikely.

Even then, it would not materially change the punchline, which is “It’s tough to identify future superstars, draft them, and keep them.” While the Draft is the primary means of entry for future superstars, they tend to win titles on teams that acquire them after the Draft or they are drafted later in the Lottery picks. This points to inefficiency in the GM pool in the NBA. Said another way, not all picks are used to full potential, something that is widely known.

This also raises a question of if the teams that keep get superstars later in the Draft are able to actualize more potential because of better staff, facilities, culture, leadership, and the luxurious necessity of patience.

Regardless, unless you can use the pick on that superstar, develop that superstar, and keep that superstar long enough to win a title, what use is the pick to those who would rather win than lose-so-they-can-win? Remember, “winning more games” is a discounted reason and is discounted by those advocating losing winnable games.

One last `nod’ to this losing-is-winning point-of-view is that perhaps the above metric is limited in that is takes into account only titles won, not legitimate chances at titles. This is a fair question. Cleveland made it to the Finals with LeBron and had a good team, but got swept. Looking at the 4-3 losses in the finals, we add 4 teams in the Lottery era and add Ewing as a first pick, and he was acquired in an era when the Lottery was not weighted. That’s it. Adding in 4-2 series, digging through injury issues, etc. can all be done to puff up the number, but, in the end, those things affect all teams and dampen the effect of high Lottery picks on teams, so they just can not be set aside in a fit of optimism or charity.

The more you slowly dig, the more the picture becomes clear: there’s just so much more to winning a title than drafting. In fact, it seems far more likely that the superstars win titles after being acquired by other means by teams that did not have the chance to draft early, which brings the discussing back to the confounding considerations above.

If anything, the New Orleans Hornets defied the odds and selected Anthony Davis in the most recent Draft. History says the identification and drafting being done bring focus to keeping him here. He’s essentially under control for around 8 years, so the team has that long to turn itself around in other ways and prove to be a winner with perpetual chances to win titles, not a loser that has to wait (too long) for the dice to come up just right (again).

Balancing the Books

The typical argument advocating losing tends to emphasize the (untrue) benefits of the Lottery and the costs of winning games now, usually with respect the (untrue) benefits of the Lottery. Genuflection to idea that winning is good is sometimes given, but it is nearly immediately dismissed as dwarfed by the other already mentioned costs and (untrue) benefits.

Let’s start with the benefits of winning, and let’s bring this around the Hornets winning, particularly as to how it will benefit the Pelicans. In the recent win over Boston, completing the season sweep, there were numerous examples of clear growth by the players, perhaps even growing during the game.

Anthony Davis put a move or two on Kevin Garnett, and that game-winning tip-in was an exemplar of just about everything one could want in a basketball player with a sprinkling of powdered sugar on top.

Vasquez, though limited is his passing ability and efficiency by the Celtics defense, found ways to get involved with others handling the ball, ending with a more efficient scoring night than normal.

Anderson brutalized them.

Eric Gordon showed more determination than he has to date (to my eye). He made key passes, and though he lost control of the ball, not always losing possession, he recovered sufficiently on the last possession and then drove to the basket rather than settling for a jumper.

For the first time since his opening game against Phoenix in 2011, I actually enjoyed a Gordon play in a pure fashion.

Sure, he missed, but that’s not the point. Neither is Davis’ follow-up (‘t’was good, but this is the Gordon bit). Gordon may have had some kind of breakthrough. If so, what’s that worth?

The 236,160 seconds a player has available to him in an NBA regular season are all resources. They are precious resources. This is less than 66 hours . . . less than 3 days . . . way less than it takes to watch Lost. They can be used for a number of things, but player development and team development are two key uses for them. These seconds have been used for both purposes all season here in New Orleans, and it shows. It’s paying off.

Rivers’ season was likely ended just as he turned a corner (unlikely it was the corner), and many Hornets fans lament the loss in a way that was likely inconceivable in December. So why would be do the same thing to rest of the players and the team as a whole willfully? Well, if there was enough benefit, that would be a reason why.

Is there? Does it outweigh the opportunity cost described here?

Additionally, it’s not like a team that is squarely in the Lottery mix can effectively translate “trying” into “winning.” If they could, this article might be about the playoffs instead . . . .

This is not even broaching the benefits to the coaches and staff in terms of evaluating who to keep on the team going forward; deciding how best to use players; showcasing particular players for trade; building a reputation around the NBA; establishing a team identity, a franchise culture; selling tickets, concessions, parking, and advertisements; and more; with the cost of losing basically being the opportunity cost established here plus the additional revenue being pushed out of the franchise by digging the hole even deeper with fans and sponsors. A bad season here and there is expected, especially given the situations facing the Hornets over the past several years. Repeated bad seasons start to have difficult-to-repair kinds of damage to the franchise.

Now a closer-to-accurate calculation can be performed by comparing the costs and benefits of losing now to those of winning now rather than viewing the situation through the knothole of the empty rhetoric surrounding the Draft.

Back to Reality

I do not really care one way or the other what anyone concludes from their personal, but correctly formed, calculation regarding the losing-is-winning perspective, but the incorrect premises and calculations are frustrating. But, evaluation of a strategy and forming a favorable opinion does not mean the team embraces this.

It’s been said . . . sometimes in jest, sometimes not . . . that the Hornets are losing some games on purpose. The Boston game alone contradicts this. Davis was reported to be sick and said he was still so following the game, but he played. He was sitting with an irritated shoulder near the end of the game, but returned with 2:33 left to play and had the winning tip-in while between two Celtics. The Hornets managed the clock well at the end after digging themselves out of a double digit hole after holding the Celtics to just 12 third quarter points and repeating the feat in the fourth save for 4 minute outburst by Paul Pierce.

It helps to make light of disappointing situations, so discussing losses as if they are the preferred product has its place, but overdoing it is disrespectful to the people who are not trying to lose. Also, some teams have nothing to gain by losing games at the end of the season (e.g. 2011-2012 Charlotte Bobcats), but they can not simply stop doing so because they are just that bad.

Do teams look at winning each and every game as the top priority of the franchise? No. Are points in the season reached where players’ values as assets, either in trade or on the court next season, outweigh their value this offseason? Sure. Does the Lottery play a role in this? It better. But something likely benefiting lottery odds does not mean that it was instituted to do so.

If a team decided to implement this strategy, doing so late in the season limits its benefit while not reducing costs by the same amount since ending on low note may affect offseason transactions in terms of talent and raw dollars from fans and sponsors. Plus, whatever reason a given team has for implementing this strategy, then those reasons would apply to other teams, particularly those that would be hurt by the team pushing to lose. So if the reasons are sound for the first team, they are even more sound for the team that may have its losing surpassed, so, logically, they should embrace the strategy and would likely be more successful since they were worse before the decision was made and have a head start on the losing. This would then limit the benefit of losses further as a result of the group behaviors, as the quick game theoretic qualitative calculation shows (see, I don’t mind qualitative arguments).

Since winning games is not choice freely made by a team unilaterally, and losing purposely is more of a choice but can not be made without a successful reactive move from competitors, it shows that playing all games with consistent effort is an equilibrium. If winning a generic game is better than losing it, then this equilibrium point is optimal, at least locally, in the game theoretic sense. It may not be globally optimal.

Since all games throughout the season contribute to the Lottery position, then a team deciding to go after a high draft choice should give that consistent effort all season. Sadly, those teams still need 3 seasons to have better than an even chance of attaining a top draft pick. Benefit aside, that is how to best achieve it, not to try to lose games near the end of the season in an attempt to `maximize’ something that is may not be maximizable or worth maximizing.

It should be noted that this breaks down at the very end of seasons. With, say, a game left, it is much more difficult do determine generically which `move’ is superior. With such small games, there is no long-run to consider, and these analyses just do not apply.

Breaking the Cycle

A rational look at the larger picture of the franchises in the NBA, their histories, and the structure of the draft lottery shows that rooting for losses late in a season is irrational at worst and distracting at best. While a team who tries to lose games will eventually be rewarded, it is not a winning strategy in any sense. It’s best to just stick to the season plan whether that be to win games, lose games, or ignore the outcomes and work on the processes, team development, and player development.

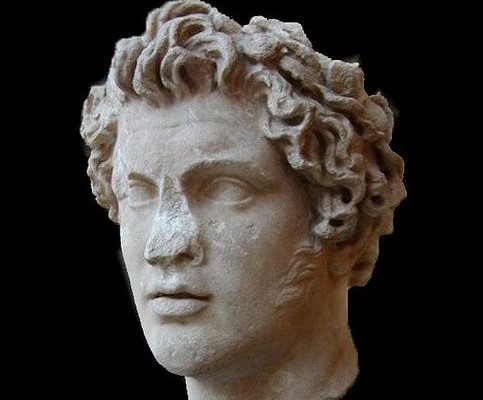

The picture associated with this post is a bust of Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus is the eponym of a Pyrrhic victory. Pyrrhus was a King of Epirus (in modern-day Greece and Albania), who, in a campaign in Italy against the Romans (see where this is going?), won a victory that was so costly, he was reported to have said that another such victory would end him. Thus, a Pyrrhic victory is one where a battle is won in a way that costs the war. This particular bust is fun in that it inspires the idea of cutting one’s nose off to spite one’s face . . . a very similar sentiment.

The data shows these losses that some advocate for some much may be just such victories. They may not be, of course, as there is no predicting randomness.

That’s no reason to tempt fate, however, or the dice.

Above it was noted how the Hornets need should approach the rest of the season. The New Orleans Pelicans may end up with an early Draft pick or one a little late for some. Regardless, they need to focus on using the draft pick most effectively. They need to get into this practice facility as soon as possible. They need to get control of the Eric Gordon situation so that not only is his value as a player and an asset maximized, but so the team identity can form cleanly. This is with respect to perpetual notion that both Gordon and the Hornets want to part ways and to Gordon’s knee surgery recovery. They need to continue to churn the roster, sifting through players for assets that can be had at on reasonable deals and assets that can appreciate, continuing the push for a title run in a few years’ time.

Drafting a superstar is by no means easy, but this is the second time the New Orleans Hornets have done so. That guy left, however, which is what started this whole mess all over again. Of course, having a superstar that might leave is superior to not having one at all. Still, the Hornets, and their fans, need to get out of Draft mode and get into the mode of keeping that superstar. He’ll get maximum money, and other markets will have allure that New Orleans can not duplicate. They’ll have to form their own. They can, of course, but this reputation needs to form and spread.

Quickly.

Winning is what will do that.

Coincidentally, that also helps in the title hunt: winning.

Go figure.

9 responses to “Untying Winning and Losing”

We played to win at the end of last season, and that seemed to work out OK for us. We’ve got lots of cap flexibility and some solid core players. Just play out the season and let the ping-pong balls fall where they may. . .

I think fans are justifiably concerned about their team not finishing low enough to get a top X pick. And I think x in this draft is generally 3 or 4.

The problem is this victory over Boston took us from 3rd to worst record to a three way tie for 4th to worst, and 3rd to worst record has a 47% chance of drafting in the top 3 and a 70% chance of drafting in the top 4 while the 5th worst record, a reasonable proxy for the record of the teams in a three way tie for 4th to worst, only has a 27% chance of drafting in the top 3 and a 0% chance of getting the 4th pick. So the specter of a finish like the current standings nearly cuts the chance of a top 3 pick in half and the chance of a top 4 pick by 2/3rds. That is a real concern.

And what is so great about a top 5 pick?

This article by Ryan explains that pretty well: http://www.hornets247.com/2012/06/22/the-value-of-a-draft-pick-and-the-hornets-picks/

This year the eye test tells me it may be best to pick in the top 3 or 4, before the college talent starts to drop off.

Getting the best players is something one might interested in. Ever looked to see how many such picks help their drafting team win a title?

Not many.

Great piece 42.

Wow, I was going to try and put a fly in your ointment by adding that Kobe, though technically drafted by us, was traded before ever playing for the Hornets. Then I remembered he was selected 13th. Paul Pierce was 10th. Dirk went 9th. I guess those all fall under the GM whiffs and misevaluation of talent (or perhaps there is more about the development of the talent).

I guess the only caveat I would add (which is purely pedantic) is that I think that the learning, the cohesion of the individuals into a unit, the parts of the game that can be improved over time may, but don’t necessarily correlate directly with winning. If we win it doesn’t mean our guys figured anything out, and if we lose it doesn’t mean we didn’t figure out how to improve. Its part of the NBA fan I see often. I would rather my team lose playing “the right way”(whatever subjective way you define that), than win playing “the wrong way”(samesies).

That said, you’ve added more cognitive dissonance than I already had about rooting for losses but I’ll continue. Maybe its the advancements in scouting, maybe its because in Demps I trust, but I would rather we have at least a marginal percentage of picking the guy we think helps us more than the other. As much as history shows us that the other GM’s have failed, I think that we can make a choice here that impacts the difference between winning and losing enough in the future to justify me getting on board with the tank.

Playing to win does not always lead to wins. That is fine.

Playing to lose is the proposal by some.

Playing to lose should NEVER be the goal of a team. A team should never take the mentality to lose games. Its stupid, if you’re a real competitor you would never want to actually lose when you’re on the court. That goes for coach and player.

[…] so much focus on trying to get a good slot in the lottery, it behooves one to look at how much drafting in the top 5 has actually helped teams go on to win titles. As it turns out, not so much. So, there’s more to this then just drafting high and waiting […]